« 2006 April | Main | 2006 February »

Tuesday, March 28, 2006

New Market

Tuesday, March 21, 2006

Night Driving (w/addendum)

Tuesday, March 07, 2006

Homeland Security is a Joke

Picking Up Litter

New Market

One of the watch officers sent out a few emails

on SIPRNET, the secure internet protocol router network, calling it Operation

New Market Garden. He was confusing the Civil War battle of New Market with the

Second World War battle of Operation Market Garden and somehow combined them

into one name. I sent him a chat poking him in the ribs and told him the

correct name. I think he graduated from the Virginia Military Institute which

fought the battle of New Market so he was pretty embarrassed. I laughed with

him over his faux pas.

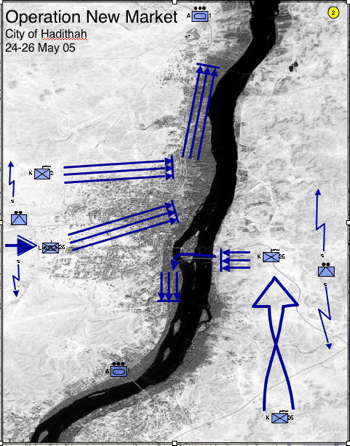

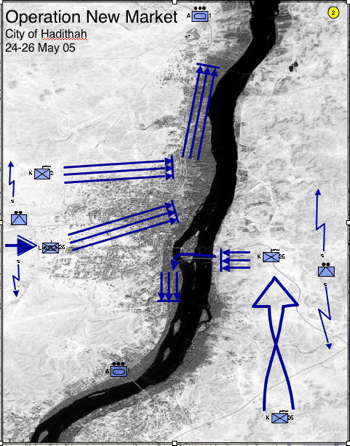

It's good to laugh about these things. New Market was the most kinetic operation I was on. Some of our companies had been in much worse west of us near the Syrian border, but not with our battalion. Major Steve White did a great job planning this operation, going through all the school house planning steps and ensuring that we had a solid plan. The maneuver elements were three companies. We had Kilo Company, 3d Battalion, Second Marines. We also had Lima Company from our battalion, 3d Battalion, Twenty-fifth Marines coming from the west. Finally we had Kilo Company from 3/25 who came up from Camp Hit and did a helo insert on the east side of the river. Alpha Company, 1st Tank Battalion screened north and south. Weapons company from 3/25 screened east and west.

The comm platoon was getting good at supporting the battalion staff on these operations. Each time out we raised the bar. This time we put an EPLRS network in place, using line of sight UHF radio routers, kind of like your home wireless network on steroids, and connected our COC to our data network back at Haditha Dam, our battalion headquarters. Everyone yawned when I told them we could have SIPRNET on the operation. Either they didn't believe it possible, or they didn't grasp the utility of the venture.

It's good to laugh about these things. New Market was the most kinetic operation I was on. Some of our companies had been in much worse west of us near the Syrian border, but not with our battalion. Major Steve White did a great job planning this operation, going through all the school house planning steps and ensuring that we had a solid plan. The maneuver elements were three companies. We had Kilo Company, 3d Battalion, Second Marines. We also had Lima Company from our battalion, 3d Battalion, Twenty-fifth Marines coming from the west. Finally we had Kilo Company from 3/25 who came up from Camp Hit and did a helo insert on the east side of the river. Alpha Company, 1st Tank Battalion screened north and south. Weapons company from 3/25 screened east and west.

The comm platoon was getting good at supporting the battalion staff on these operations. Each time out we raised the bar. This time we put an EPLRS network in place, using line of sight UHF radio routers, kind of like your home wireless network on steroids, and connected our COC to our data network back at Haditha Dam, our battalion headquarters. Everyone yawned when I told them we could have SIPRNET on the operation. Either they didn't believe it possible, or they didn't grasp the utility of the venture.

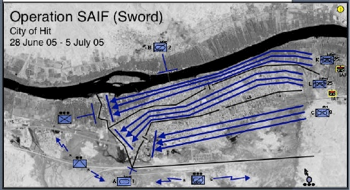

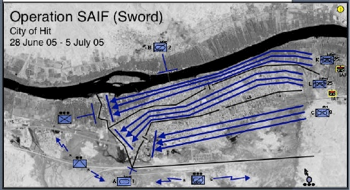

We had been testing the EPLRS network extensively

before the operation and I knew it would work. The success in this operation is

what convinced me to make bolder promises in our later Operation

Sword. As promised, EPLRS worked fabulously and Steve raved for weeks

afterward about this new capability.

I couldn't have been more impressed by the comm platoon Marines. The comm chief, GySgt Eason, was brilliant in training them and preparing them and the equipment for the operation. He stayed behind at the dam this time and supported the back end of the comm systems, especially data and EPLRS. LCpl J. A. Williams was tossed in, reluctantly at first, and was told he had to make EPLRS work with minimal training. This is when native intelligence and having good character becomes so important to key positions. J.A. wasn't anxious at all about going on the operation, but never balked and took his responsibility with the greatest seriousness. Although I lavished great praise on him, I don't think he really bought into how impressed I was at how he jumped in and made everything work. With Marines like him we will never lose any war.

And he wasn't alone. Both of the sergeants were tremendously strong, I felt like Sgt Byrnes and Sgt Francis were like Ruth and Gehrig. Sgt Francis was the radio chief and his energy was absolutely endless. They set the standard for all the radio operators and made the radio watch function with crisp professionalism. They made my job boring, I had very little to do except increase my demands for higher and higher standards, which they never failed to meet.

But not everything was rosy on this operation. Shortly after the companies entered the city they were attacked. My friend Capt Ray Lopes, a fellow Portuguese and in my company at The Basic School in 1985 was shot in the hip, and another Marine was injured. Around the same time Maj Crocker was killed by an RPG round.

Shortly after we took over the neighborhood technical school for our combat operations center, an amtrac hit a mine 30 yards from us. Then came several mortar rounds. Major Catalano, the Sergeant Major, a few gunnery sergeants and I patrolled outside the perimeter of the school a few times to find the mortar impact craters. By analyzing the crater you can get a general idea of which direction it was fired from. It took a long time to find where the rounds landed. I think there were about seven rounds the first salvo, and there were two or three attacks, maybe more.

At one point when things were hectic, the air officer was calling in air strikes, the ops officer was directing the companies, amtracs were blowing up, tanks getting shot at by mortars and roaring around trying to find the mosquitos shooting at them, the battalion surgeon decided that some of the casualties were too serious to drive the 30 minutes to the dam for medical evacuation, our preferred evac point, and called for the blackhawks to fly directly to the COC for evac.

With the officers in operations so busy, I went out to make sure everything was ready for the medevac. People were jumpy because of the mortar attacks, though no mortars hit us then. I commandeered some Marines and assigned them to be stretcher bearers. I don't suppose we would have had trouble finding any, but I wanted them identified ahead of arrival so we didn't have to go looking for any. I think we needed three or four teams and I have no idea who some of those Marines were, I just grabbed them and told them to grab stretchers.

While I was busy doing that, I was out with some of my comm platoon Marines in the courtyard. I think we were discussing how the helo would be landing, and I heard the characteristic crack of bullets passing by. Later we estimated it was about 21 shots, most wildly missing, but they started getting closer and closer. When a bulllet passed just a few feet from me and another between two of my Marines, we suspended our medevac preparations and got under cover. We finished getting the area ready for medevac a few minutes later when the shooting stopped.

Maybe if you get shot at a lot and see the bullets hitting people, your reaction might be a bit more vigorous. Maybe we were just too oblivious. But mostly we just shrugged off the small arms fire and kept about whatever we were doing until we could no longer ignore how close they were getting.

I remember looking towards the direction the shots came from, and seeing nothing for a few kilometers except for two houses about 500 meters away. The rules of engagement prohibited returning fire unless we could positively identify the shooter. So we didn't shoot back from the courtyard, but our snipers returned fire for us. My whole time in Iraq, in all the operations I went on, I never fired a shot in anger. But I suppose as a staff officer that is as it should be.

Haditha had become a center of insurgent operations after they lost Fallujah and Ramadi. Fallujah was almost entirely destroyed and was completely pacified (there's a lesson in there somewhere) and Ramadi was occupied. The muj were active in Ramadi, but their freedom of movement was severely hampered. Haditha was one of their last holds along the Euphrates River and became a primary point for them to transit across the river to northern and eastern Iraq from Syria. New Market disrupted their operations, kept them guessing what we were doing next, and cost them a lot of equipment, money, and people.

From a strategic standpoint, we were waiting for trained Iraqi army units to join us before we established a permanent presence there, so when we left the enemy was able to regroup, retrench and again terrorize the people living there. Although we disrupted enemy activity, one side effect was to shake the locals' trust in our willingness to stay and help free them from the thugs. I suppose it could be argued that it might have been better to leave the city alone until we could go and occupy it permanently, and many have said as much.

I don't agree. I don't care too much about Iraqis that allow terrorists to live among them, no matter the threats, and I'd much rather keep the enemy reacting to our plans and not living comfortably where they can relax and plan more and more ambitious attacks on us.

New Market was no more than a raid, and it wasn't until after we left that the battalion replacing us was able to finally make a permanent presence there, but New Market was successful in keeping the enemy rocking back on their heels and licking their wounds. They might have bragged to the Iraqis that they "threw us out of the city in a big defeat" and maybe some Iraqis believed it, but the enemy themselves knew better because they were usually reacting to our operations and struggling to keep their own forces from collapsing.

That's what the USMC got out of the operation. What I got was something entirely different. I had friends shot, killed, I saw amphibious tractors destroyed nearby, I was shot at by the most prolonged mortar engagements I saw my entire time overseas, I was shot at by small arms fire. Yet I never saw a single Marine afraid.

Not once did I see a single Marine balk at going outside the wire. Not once did any express fear. Even the men in weapons company who repeatedly got hit by roadside bombs were fearless. Even after getting their vehicles blown out from under them on several occasions, even in MAP-7 where so many were killed or shipped home on a stretcher that only a handful were original members of the platoon, not once did I see a single Marine act with anything but enthusiasm when heading out on a mission. The importance to me of Operation New Market was that I knew that although Marines of earlier generations were in worse wars and experienced far more hellish combat, I knew that the Marines we have today are their equals. After New Market, if I ever had any doubts about the current breed of Marines they were fully dispelled. I was proud to be among heros every day, and ever more determined to not let them down.

I couldn't have been more impressed by the comm platoon Marines. The comm chief, GySgt Eason, was brilliant in training them and preparing them and the equipment for the operation. He stayed behind at the dam this time and supported the back end of the comm systems, especially data and EPLRS. LCpl J. A. Williams was tossed in, reluctantly at first, and was told he had to make EPLRS work with minimal training. This is when native intelligence and having good character becomes so important to key positions. J.A. wasn't anxious at all about going on the operation, but never balked and took his responsibility with the greatest seriousness. Although I lavished great praise on him, I don't think he really bought into how impressed I was at how he jumped in and made everything work. With Marines like him we will never lose any war.

And he wasn't alone. Both of the sergeants were tremendously strong, I felt like Sgt Byrnes and Sgt Francis were like Ruth and Gehrig. Sgt Francis was the radio chief and his energy was absolutely endless. They set the standard for all the radio operators and made the radio watch function with crisp professionalism. They made my job boring, I had very little to do except increase my demands for higher and higher standards, which they never failed to meet.

But not everything was rosy on this operation. Shortly after the companies entered the city they were attacked. My friend Capt Ray Lopes, a fellow Portuguese and in my company at The Basic School in 1985 was shot in the hip, and another Marine was injured. Around the same time Maj Crocker was killed by an RPG round.

Shortly after we took over the neighborhood technical school for our combat operations center, an amtrac hit a mine 30 yards from us. Then came several mortar rounds. Major Catalano, the Sergeant Major, a few gunnery sergeants and I patrolled outside the perimeter of the school a few times to find the mortar impact craters. By analyzing the crater you can get a general idea of which direction it was fired from. It took a long time to find where the rounds landed. I think there were about seven rounds the first salvo, and there were two or three attacks, maybe more.

At one point when things were hectic, the air officer was calling in air strikes, the ops officer was directing the companies, amtracs were blowing up, tanks getting shot at by mortars and roaring around trying to find the mosquitos shooting at them, the battalion surgeon decided that some of the casualties were too serious to drive the 30 minutes to the dam for medical evacuation, our preferred evac point, and called for the blackhawks to fly directly to the COC for evac.

With the officers in operations so busy, I went out to make sure everything was ready for the medevac. People were jumpy because of the mortar attacks, though no mortars hit us then. I commandeered some Marines and assigned them to be stretcher bearers. I don't suppose we would have had trouble finding any, but I wanted them identified ahead of arrival so we didn't have to go looking for any. I think we needed three or four teams and I have no idea who some of those Marines were, I just grabbed them and told them to grab stretchers.

While I was busy doing that, I was out with some of my comm platoon Marines in the courtyard. I think we were discussing how the helo would be landing, and I heard the characteristic crack of bullets passing by. Later we estimated it was about 21 shots, most wildly missing, but they started getting closer and closer. When a bulllet passed just a few feet from me and another between two of my Marines, we suspended our medevac preparations and got under cover. We finished getting the area ready for medevac a few minutes later when the shooting stopped.

Maybe if you get shot at a lot and see the bullets hitting people, your reaction might be a bit more vigorous. Maybe we were just too oblivious. But mostly we just shrugged off the small arms fire and kept about whatever we were doing until we could no longer ignore how close they were getting.

I remember looking towards the direction the shots came from, and seeing nothing for a few kilometers except for two houses about 500 meters away. The rules of engagement prohibited returning fire unless we could positively identify the shooter. So we didn't shoot back from the courtyard, but our snipers returned fire for us. My whole time in Iraq, in all the operations I went on, I never fired a shot in anger. But I suppose as a staff officer that is as it should be.

Haditha had become a center of insurgent operations after they lost Fallujah and Ramadi. Fallujah was almost entirely destroyed and was completely pacified (there's a lesson in there somewhere) and Ramadi was occupied. The muj were active in Ramadi, but their freedom of movement was severely hampered. Haditha was one of their last holds along the Euphrates River and became a primary point for them to transit across the river to northern and eastern Iraq from Syria. New Market disrupted their operations, kept them guessing what we were doing next, and cost them a lot of equipment, money, and people.

From a strategic standpoint, we were waiting for trained Iraqi army units to join us before we established a permanent presence there, so when we left the enemy was able to regroup, retrench and again terrorize the people living there. Although we disrupted enemy activity, one side effect was to shake the locals' trust in our willingness to stay and help free them from the thugs. I suppose it could be argued that it might have been better to leave the city alone until we could go and occupy it permanently, and many have said as much.

I don't agree. I don't care too much about Iraqis that allow terrorists to live among them, no matter the threats, and I'd much rather keep the enemy reacting to our plans and not living comfortably where they can relax and plan more and more ambitious attacks on us.

New Market was no more than a raid, and it wasn't until after we left that the battalion replacing us was able to finally make a permanent presence there, but New Market was successful in keeping the enemy rocking back on their heels and licking their wounds. They might have bragged to the Iraqis that they "threw us out of the city in a big defeat" and maybe some Iraqis believed it, but the enemy themselves knew better because they were usually reacting to our operations and struggling to keep their own forces from collapsing.

That's what the USMC got out of the operation. What I got was something entirely different. I had friends shot, killed, I saw amphibious tractors destroyed nearby, I was shot at by the most prolonged mortar engagements I saw my entire time overseas, I was shot at by small arms fire. Yet I never saw a single Marine afraid.

Not once did I see a single Marine balk at going outside the wire. Not once did any express fear. Even the men in weapons company who repeatedly got hit by roadside bombs were fearless. Even after getting their vehicles blown out from under them on several occasions, even in MAP-7 where so many were killed or shipped home on a stretcher that only a handful were original members of the platoon, not once did I see a single Marine act with anything but enthusiasm when heading out on a mission. The importance to me of Operation New Market was that I knew that although Marines of earlier generations were in worse wars and experienced far more hellish combat, I knew that the Marines we have today are their equals. After New Market, if I ever had any doubts about the current breed of Marines they were fully dispelled. I was proud to be among heros every day, and ever more determined to not let them down.

Tuesday, March 21, 2006

Night Driving (w/addendum)

It was time to go. It was late at night, and we

were loading up our vehicles to begin movement to our attack positions.

Normally I rode in the command and control vehicle but for some reason the

Operations Officer directed me to ride in his vehicle. Everything was going as

planned. Everything except one thing. My

thing.

Normally he is extremely even tempered. I admire Steve White more than just about any officer I've ever known. Professional, inclusive, brings everyone onto his team with respect and provided consistent, decisive leadership. This was the only time he lost his temper with me.

"So we're screwed! We've got no comm."

Normally he is extremely even tempered. I admire Steve White more than just about any officer I've ever known. Professional, inclusive, brings everyone onto his team with respect and provided consistent, decisive leadership. This was the only time he lost his temper with me.

"So we're screwed! We've got no comm."

Surprised by his anger, I responded in kind and

immediately regretted it. "How do you think that? We've got VHF and SatComm,

just like always. And we'll get data running soon."

Steve was angry that our CONDOR data network, which no one had ever used yet outside of testing, wasn't yet functional. It was an experimental system that we only had in our possession for a few days and only got a critical cable an hour earlier. But now we were rolling into battle and he believed my early promises for delivering miracles. I normally didn't promise anything that I didn't know I would deliver. This time I miscalculated. It was much harder to get this untested equipment working than I had anticipated. But we had all our other systems up and running and this system was just an extra one. It was a very powerful extra system, but nothing we had ever needed before.

Steve is a thorough professional, sloughed off my retort, and we all climbed in the up-armored Humm-vee and moved out in darkness to our initial combat operations center (COC) location. Really, it was nothing more than an open field nestled among some small hills in the desert just south of the city of Hit.

I was riding in the right seat up front, one of my radio operators was driving, while Steve and Woody, our air officer, were in the back seats. It was a pitch black, moonless night and I couldn't see a thing. We drove with our lights out, the driver wearing night vision goggles. I sat in the humm-vee with nothing to see except glowing lights on the radios.

But then something else didn't go according to plan. Some of our new up-armored humm-vees had bad fuel controls. These trucks had bigger engines to compensate for the extra armor and the vehicle I was in was so new that even the air conditioner worked great. But the fuel controls presented a problem. If the ground was flat the truck was merely sluggish. But if there were any rise in terrain, anything as mountainous as a speed bump, if we didn't already have some forward momentum, we couldn't move. It was almost comical.

Except that it wasn't.

After we got south to where Route Bronze and Route Uranium split, we turned north and drove through the desert to our night's destination. Now it was the driver's time for expressing frustration. The dust in Iraq's deserts in the summertime is often called moon dust because it is light and puffy like aerated talcum powder. Sure enough, as soon as we got off road the dust billowed and obscured everything. We had to drive exclusively by the bright night vision reflectors on the vehicles ahead of us. But whenever we hit a small rise in the terrain, we fell further and further behind. We lost our way several times, dragging along all the vehicles behind us.

Steve dug out a set of night vision goggles so I could help the driver find and stay in contact with the leading vehicles. Several times we had to stop and investigate why we seemed stuck. We didn't yet understand the fuel control problem. I also had to wander out in front, to link up with the vehicles in front who had stopped to wait for us. It was slow going.

All this time, our communications chief was continuing to talk via satellite to get our data systems working.

We finally reached where we were going, and anxiously monitored the progress of the three line companies -- K/3/25, L/3/25, and the army's magnificent Company C from the "first of the ninth" regiment -- as they entered the city. Weapons company screened to the north, and a company from the 2d Light Amphibious Reconnassaince battalion screened east and west.

I can't describe the elation I felt when the sun rose and the murky, dusty desert turned into a bright and clear day, with the city spread out below us. The mystery was revealed, for the first time I saw where we were and where we were going. About that time, our data network came up, in a limited way, and we started getting email from our amtraks, Lima Company, and our advanced logistics operations center. In a couple more hours, we broke the code on connecting to the regular military classified network.

Steve finally got his data package, and stayed in touch with everyone through our chat rooms. The regimental staff continuously stayed in touch to a degree never before possible. Bandwidth was limited, but usable, and we were able to provide a much clearer picture of operations to higher headquarters than ever before. The system was finicky, and took a lot of attention to keep it running, but it worked.

Shortly after sunrise we moved into the city, and moved to three more locations, finally settling in what became Firm Base 1. I remained there for over two weeks with the battalion staff until we relinquished it to Lima Company and returned to Camp Hit, five miles north of the city to continue on going control from there.

*******

Addendum. Skyler's dad made a comment that it was too bad we had a bad day. Here was my response.

It wasn't really a bad day. Everything went well except that my humm-vee was a dog. We were stressed because we thought we were going into a battle that would be like Fallujah. We fully expected a very bloody greeting. We had gotten rough welcomes in Hadithah and Haqlaniyah, and Barwana and most other places. Only Kubaysa was quiet. Hit was a place that had very bad ambushes on the battalion before us and we'd not been there since. So we were a bit jumpy.

After we moved from that position we drove into the city. The line companies had advanced through the area and cleared a building for us to use as a headquarters. But they were long gone by the time we got there. I was the first one out of the vehicle when we arrived and the S-3 and air officer were busy directing the battle. So I took it upon myself to clear the building. Me and two other Marines did old fashioned infantry stuff, busting the doors open and making sure no muj were there. It was empty, but I had fun playing John Wayne, if only for a brief time on a building that was cleared once already.

I really had a ball over there. I wonder if I'll ever get to do it again.

Steve was angry that our CONDOR data network, which no one had ever used yet outside of testing, wasn't yet functional. It was an experimental system that we only had in our possession for a few days and only got a critical cable an hour earlier. But now we were rolling into battle and he believed my early promises for delivering miracles. I normally didn't promise anything that I didn't know I would deliver. This time I miscalculated. It was much harder to get this untested equipment working than I had anticipated. But we had all our other systems up and running and this system was just an extra one. It was a very powerful extra system, but nothing we had ever needed before.

Steve is a thorough professional, sloughed off my retort, and we all climbed in the up-armored Humm-vee and moved out in darkness to our initial combat operations center (COC) location. Really, it was nothing more than an open field nestled among some small hills in the desert just south of the city of Hit.

I was riding in the right seat up front, one of my radio operators was driving, while Steve and Woody, our air officer, were in the back seats. It was a pitch black, moonless night and I couldn't see a thing. We drove with our lights out, the driver wearing night vision goggles. I sat in the humm-vee with nothing to see except glowing lights on the radios.

But then something else didn't go according to plan. Some of our new up-armored humm-vees had bad fuel controls. These trucks had bigger engines to compensate for the extra armor and the vehicle I was in was so new that even the air conditioner worked great. But the fuel controls presented a problem. If the ground was flat the truck was merely sluggish. But if there were any rise in terrain, anything as mountainous as a speed bump, if we didn't already have some forward momentum, we couldn't move. It was almost comical.

Except that it wasn't.

After we got south to where Route Bronze and Route Uranium split, we turned north and drove through the desert to our night's destination. Now it was the driver's time for expressing frustration. The dust in Iraq's deserts in the summertime is often called moon dust because it is light and puffy like aerated talcum powder. Sure enough, as soon as we got off road the dust billowed and obscured everything. We had to drive exclusively by the bright night vision reflectors on the vehicles ahead of us. But whenever we hit a small rise in the terrain, we fell further and further behind. We lost our way several times, dragging along all the vehicles behind us.

Steve dug out a set of night vision goggles so I could help the driver find and stay in contact with the leading vehicles. Several times we had to stop and investigate why we seemed stuck. We didn't yet understand the fuel control problem. I also had to wander out in front, to link up with the vehicles in front who had stopped to wait for us. It was slow going.

All this time, our communications chief was continuing to talk via satellite to get our data systems working.

We finally reached where we were going, and anxiously monitored the progress of the three line companies -- K/3/25, L/3/25, and the army's magnificent Company C from the "first of the ninth" regiment -- as they entered the city. Weapons company screened to the north, and a company from the 2d Light Amphibious Reconnassaince battalion screened east and west.

I can't describe the elation I felt when the sun rose and the murky, dusty desert turned into a bright and clear day, with the city spread out below us. The mystery was revealed, for the first time I saw where we were and where we were going. About that time, our data network came up, in a limited way, and we started getting email from our amtraks, Lima Company, and our advanced logistics operations center. In a couple more hours, we broke the code on connecting to the regular military classified network.

Steve finally got his data package, and stayed in touch with everyone through our chat rooms. The regimental staff continuously stayed in touch to a degree never before possible. Bandwidth was limited, but usable, and we were able to provide a much clearer picture of operations to higher headquarters than ever before. The system was finicky, and took a lot of attention to keep it running, but it worked.

Shortly after sunrise we moved into the city, and moved to three more locations, finally settling in what became Firm Base 1. I remained there for over two weeks with the battalion staff until we relinquished it to Lima Company and returned to Camp Hit, five miles north of the city to continue on going control from there.

*******

Addendum. Skyler's dad made a comment that it was too bad we had a bad day. Here was my response.

It wasn't really a bad day. Everything went well except that my humm-vee was a dog. We were stressed because we thought we were going into a battle that would be like Fallujah. We fully expected a very bloody greeting. We had gotten rough welcomes in Hadithah and Haqlaniyah, and Barwana and most other places. Only Kubaysa was quiet. Hit was a place that had very bad ambushes on the battalion before us and we'd not been there since. So we were a bit jumpy.

After we moved from that position we drove into the city. The line companies had advanced through the area and cleared a building for us to use as a headquarters. But they were long gone by the time we got there. I was the first one out of the vehicle when we arrived and the S-3 and air officer were busy directing the battle. So I took it upon myself to clear the building. Me and two other Marines did old fashioned infantry stuff, busting the doors open and making sure no muj were there. It was empty, but I had fun playing John Wayne, if only for a brief time on a building that was cleared once already.

I really had a ball over there. I wonder if I'll ever get to do it again.

Tuesday, March 07, 2006

Homeland Security is a Joke

Yeah, not a very original thought, but I wanted

to point out that when you buy an airplane ticket you merely need to look at the

boarding pass to see if you're going to be screened. If you see "SSSS" on the

boarding pass, then you will be directed like a cow to the appropriate chute and

partially disrobed publicly.

So remember that all you terrorists. Not only is homeland security not concentrating on Arabic and Asian Muslims and instead are screening 12 year old girls, you are now assured that you can know when you're being screened before you go through the "security" gate.

Don't you feel safe?

So remember that all you terrorists. Not only is homeland security not concentrating on Arabic and Asian Muslims and instead are screening 12 year old girls, you are now assured that you can know when you're being screened before you go through the "security" gate.

Don't you feel safe?

I don't.

Picking Up Litter

The weather in New Orleans was pleasant. Still

cool in the mornings, making a walk pleasant. So I walked from my quarters to

the river shore and got on the boat that carried me, like it does every morning,

across the Mississippi. It's a pleasant life here, and as people wait for the

boat and walk to and from the river, they chat and discuss work and the other

little and big things that make up their

lives.

After crossing, we disembarked and walked across the asphalt warehouse/loading dock zone to the bomb-proof buildings that house our offices. These 1950's era buildings are a testament to the cold war, labyrinthine and perplexing to all the newcomers who wander about lost for a few days.

Lost in thought, I followed behind a colonel. The grounds were generally clean and neat, as befits a military base, but there was one piece of paper on the ground, not even noticed by me for all its insignificance. The colonel bent over and picked it up, and held it until he finally reached the buiding and passed a trashcan.

Would a civilian do this? Probably not, especially if he were in the higher strata of his organization. Why is this so comman to see among senior military officers?

After crossing, we disembarked and walked across the asphalt warehouse/loading dock zone to the bomb-proof buildings that house our offices. These 1950's era buildings are a testament to the cold war, labyrinthine and perplexing to all the newcomers who wander about lost for a few days.

Lost in thought, I followed behind a colonel. The grounds were generally clean and neat, as befits a military base, but there was one piece of paper on the ground, not even noticed by me for all its insignificance. The colonel bent over and picked it up, and held it until he finally reached the buiding and passed a trashcan.

Would a civilian do this? Probably not, especially if he were in the higher strata of his organization. Why is this so comman to see among senior military officers?

I don't believe in some special ethos among

military officers, at least when it comes to trash. I don't think that military

officers have any larger than normal regard for the environment. I think the

difference is the uniform.

Now, I don't mean that being a Marine inspired him to pick up trash. What I mean is that he had a status publicly displayed, legally enforced, that is not demeaned by the act of picking up trash. He doesn't have to be so careful to project a certain status because his status is codified and rigid.

If a sales manager were walking in public near his place of work among people he didn't know, he would most likely not pick up trash without risking the perceived status he was building at work.

When I worked at Apple Computer, for the first year I worked there I thought one of the senior engineers was a janitor because I frequently saw him pushing out bins of trash from his work area. I later learned that he was a brilliant software engineer and learned to have great respect for his work, but it took a while for me to overcome that first impression.

Without a uniform or some other visible display of status, you can only rely on your actions to announce your status to others.

Uniforms are neither better nor worse than the anonymity of regular clothes, but it creates different social dynamics. Uniforms favor leaders that don't have that rare quality of presence and charisma to lead without example. Uniforms encourage subordination necessary when only one can be in charge. This is why oppressive societies, from midieval times to feudal Japan, to communist China, develop uniforms.

Uniforms oppress free people, but are necessary in the military. We might pretend that rank denotes leadership ability, but it's the uniform that encourages others to follow.

Picking up trash is not a sign of servility when you wear a uniform. It is setting the example.

I despair of having to pick up trash forever. As a major I picked up all kinds of garbage at the Marine Corps Marathon. I suspect if I were to be a general, I'd still be picking up trash.

Now, I don't mean that being a Marine inspired him to pick up trash. What I mean is that he had a status publicly displayed, legally enforced, that is not demeaned by the act of picking up trash. He doesn't have to be so careful to project a certain status because his status is codified and rigid.

If a sales manager were walking in public near his place of work among people he didn't know, he would most likely not pick up trash without risking the perceived status he was building at work.

When I worked at Apple Computer, for the first year I worked there I thought one of the senior engineers was a janitor because I frequently saw him pushing out bins of trash from his work area. I later learned that he was a brilliant software engineer and learned to have great respect for his work, but it took a while for me to overcome that first impression.

Without a uniform or some other visible display of status, you can only rely on your actions to announce your status to others.

Uniforms are neither better nor worse than the anonymity of regular clothes, but it creates different social dynamics. Uniforms favor leaders that don't have that rare quality of presence and charisma to lead without example. Uniforms encourage subordination necessary when only one can be in charge. This is why oppressive societies, from midieval times to feudal Japan, to communist China, develop uniforms.

Uniforms oppress free people, but are necessary in the military. We might pretend that rank denotes leadership ability, but it's the uniform that encourages others to follow.

Picking up trash is not a sign of servility when you wear a uniform. It is setting the example.

I despair of having to pick up trash forever. As a major I picked up all kinds of garbage at the Marine Corps Marathon. I suspect if I were to be a general, I'd still be picking up trash.