Tuesday - March 28, 2006

New Market New Market

One of the watch officers sent out a few emails

on SIPRNET, the secure internet protocol router network, calling it Operation

New Market Garden. He was confusing the Civil War battle of New Market with the

Second World War battle of Operation Market Garden and somehow combined them

into one name. I sent him a chat poking him in the ribs and told him the

correct name. I think he graduated from the Virginia Military Institute which

fought the battle of New Market so he was pretty embarrassed. I laughed with

him over his faux pas.It's good to

laugh about these things. New Market was the most kinetic operation I was on.

Some of our companies had been in much worse west of us near the Syrian border,

but not with our battalion. Major Steve White did a great job planning this

operation, going through all the school house planning steps and ensuring that

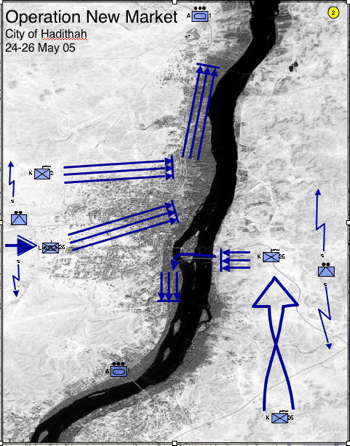

we had a solid plan. The maneuver elements were three companies. We had Kilo

Company, 3d Battalion, Second Marines. We also had Lima Company from our

battalion, 3d Battalion, Twenty-fifth Marines coming from the west. Finally we

had Kilo Company from 3/25 who came up from Camp Hit and did a helo insert on

the east side of the river. Alpha Company, 1st Tank Battalion screened north

and south. Weapons company from 3/25 screened east and

west.The comm platoon was getting good

at supporting the battalion staff on these operations. Each time out we raised

the bar. This time we put an EPLRS network in place, using line of sight UHF

radio routers, kind of like your home wireless network on steroids, and

connected our COC to our data network back at Haditha Dam, our battalion

headquarters. Everyone yawned when I told them we could have SIPRNET on the

operation. Either they didn't believe it possible, or they didn't grasp the

utility of the

venture.

We had been testing the EPLRS network extensively

before the operation and I knew it would work. The success in this operation is

what convinced me to make bolder promises in our later Operation

Sword. As promised, EPLRS worked fabulously and Steve raved for weeks

afterward about this new capability.

I couldn't have been more impressed by

the comm platoon Marines. The comm chief, GySgt Eason, was brilliant in

training them and preparing them and the equipment for the operation. He stayed

behind at the dam this time and supported the back end of the comm systems,

especially data and EPLRS. LCpl J. A. Williams was tossed in, reluctantly at

first, and was told he had to make EPLRS work with minimal training. This is

when native intelligence and having good character becomes so important to key

positions. J.A. wasn't anxious at all about going on the operation, but never

balked and took his responsibility with the greatest seriousness. Although I

lavished great praise on him, I don't think he really bought into how impressed

I was at how he jumped in and made everything work. With Marines like him we

will never lose any war.And he wasn't

alone. Both of the sergeants were tremendously strong, I felt like Sgt Byrnes

and Sgt Francis were like Ruth and Gehrig. Sgt Francis was the radio chief and

his energy was absolutely endless. They set the standard for all the radio

operators and made the radio watch function with crisp professionalism. They

made my job boring, I had very little to do except increase my demands for

higher and higher standards, which they never failed to

meet.But not everything was rosy on

this operation. Shortly after the companies entered the city they were

attacked. My friend Capt Ray Lopes, a fellow Portuguese and in my company at

The Basic School in 1985 was shot in the hip, and another Marine was injured.

Around the same time Maj Crocker was killed by an RPG round.

Shortly after we took over the

neighborhood technical school for our combat operations center, an amtrac hit a

mine 30 yards from us. Then came several mortar rounds. Major Catalano, the

Sergeant Major, a few gunnery sergeants and I patrolled outside the perimeter of

the school a few times to find the mortar impact craters. By analyzing the

crater you can get a general idea of which direction it was fired from. It took

a long time to find where the rounds landed. I think there were about seven

rounds the first salvo, and there were two or three attacks, maybe

more.At one point when things were

hectic, the air officer was calling in air strikes, the ops officer was

directing the companies, amtracs were blowing up, tanks getting shot at by

mortars and roaring around trying to find the mosquitos shooting at them, the

battalion surgeon decided that some of the casualties were too serious to drive

the 30 minutes to the dam for medical evacuation, our preferred evac point, and

called for the blackhawks to fly directly to the COC for

evac.With the officers in operations

so busy, I went out to make sure everything was ready for the medevac. People

were jumpy because of the mortar attacks, though no mortars hit us then. I

commandeered some Marines and assigned them to be stretcher bearers. I don't

suppose we would have had trouble finding any, but I wanted them identified

ahead of arrival so we didn't have to go looking for any. I think we needed

three or four teams and I have no idea who some of those Marines were, I just

grabbed them and told them to grab stretchers.

While I was busy doing that, I was out

with some of my comm platoon Marines in the courtyard. I think we were

discussing how the helo would be landing, and I heard the characteristic crack

of bullets passing by. Later we estimated it was about 21 shots, most wildly

missing, but they started getting closer and closer. When a bulllet passed just

a few feet from me and another between two of my Marines, we suspended our

medevac preparations and got under cover. We finished getting the area ready

for medevac a few minutes later when the shooting stopped.

Maybe if you get shot at a lot and see

the bullets hitting people, your reaction might be a bit more vigorous. Maybe

we were just too oblivious. But mostly we just shrugged off the small arms fire

and kept about whatever we were doing until we could no longer ignore how close

they were getting. I remember looking

towards the direction the shots came from, and seeing nothing for a few

kilometers except for two houses about 500 meters away. The rules of engagement

prohibited returning fire unless we could positively identify the shooter. So

we didn't shoot back from the courtyard, but our snipers returned fire for us.

My whole time in Iraq, in all the operations I went on, I never fired a shot in

anger. But I suppose as a staff officer that is as it should

be.Haditha had become a center of

insurgent operations after they lost Fallujah and Ramadi. Fallujah was almost

entirely destroyed and was completely pacified (there's a lesson in there

somewhere) and Ramadi was occupied. The muj were active in Ramadi, but their

freedom of movement was severely hampered. Haditha was one of their last holds

along the Euphrates River and became a primary point for them to transit across

the river to northern and eastern Iraq from Syria. New Market disrupted their

operations, kept them guessing what we were doing next, and cost them a lot of

equipment, money, and people. From a

strategic standpoint, we were waiting for trained Iraqi army units to join us

before we established a permanent presence there, so when we left the enemy was

able to regroup, retrench and again terrorize the people living there. Although

we disrupted enemy activity, one side effect was to shake the locals' trust in

our willingness to stay and help free them from the thugs. I suppose it could

be argued that it might have been better to leave the city alone until we could

go and occupy it permanently, and many have said as much.

I don't agree. I don't care too much

about Iraqis that allow terrorists to live among them, no matter the threats,

and I'd much rather keep the enemy reacting to our plans and not living

comfortably where they can relax and plan more and more ambitious attacks on

us.New Market was no more than a raid,

and it wasn't until after we left that the battalion replacing us was able to

finally make a permanent presence there, but New Market was successful in

keeping the enemy rocking back on their heels and licking their wounds. They

might have bragged to the Iraqis that they "threw us out of the city in a big

defeat" and maybe some Iraqis believed it, but the enemy themselves knew better

because they were usually reacting to our operations and struggling to keep

their own forces from

collapsing.That's what the USMC got

out of the operation. What I got was something entirely different. I had

friends shot, killed, I saw amphibious tractors destroyed nearby, I was shot at

by the most prolonged mortar engagements I saw my entire time overseas, I was

shot at by small arms fire. Yet I never saw a single Marine

afraid.Not once did I see a single

Marine balk at going outside the wire. Not once did any express fear. Even the

men in weapons company who repeatedly got hit by roadside bombs were fearless.

Even after getting their vehicles blown out from under them on several

occasions, even in MAP-7 where so many were killed or shipped home on a

stretcher that only a handful were original members of the platoon, not once did

I see a single Marine act with anything but enthusiasm when heading out on a

mission. The importance to me of Operation New Market was that I knew that

although Marines of earlier generations were in worse wars and experienced far

more hellish combat, I knew that the Marines we have today are their equals.

After New Market, if I ever had any doubts about the current breed of Marines

they were fully dispelled. I was proud to be among heros every day, and ever

more determined to not let them down.

Go Back to the Start, Do Not Collect $200 Send me your two cents

|

|